Fun British Word of the Day: Keen-willing, able, smart, eager or just about any other verb or adjective you don't feel like saying.

After a 20 minute walk into town this morning I arrived at the Isle of Wight Public Health Office, at first a disappointingly small brick building on the main street near the harbor. Resembling a DMV office more than anything, the building’s large windows that faced that street were plastered with yellowed signs advertising a range of campaigns including smoking cessation, nutrition, and the new colorectal cancer screening. However, after ringing the bell, being let in, climbing 3 staircases and navigating through several tight turns I realized the public health office was deceptively large and held offices for some 20 officials.

I first met Dr Paul Bingham who will be my temporary supervisor until Dr. Jenifer Smith, the chief medical adviser for the island, returns from vacation. Dr Bingham (though it is proper only to address him as Mr. Bingham-explained later) and I went for coffee in town near the 12th century Catholic church. As consultant to the public health office and 2nd in command behind Dr. Smith, Mr. Bingham is a shy, somewhat quiet man but is incredibly intelligent and radiates passion for his work. He trained as a surgeon, later completed an obstetrics internship in Nazareth, and has finally settled into public health on the island, where he was born.

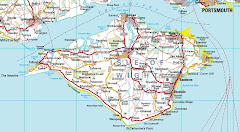

Though I’ll likely take part in some way with the Cardiovascular Prevention Research Project that I was expecting we agreed that in order to be of the most help to the office and come back to the States with a paper of my own it would be best to help elsewhere, specifically with the prisons. Several years ago, the NHS was assigned to take over prison health care as it was either absent or severely insufficient at the time. The goal then, very much like our Supreme Court Decision in 1976, was to raise standards so that all prisoners would receive care equal to that an ordinary citizen could expect. Due to its isolated geography, the island has 3 prisons and so it has been quite a challenge to find the resources for this recent expansion.

My role will be to act as a detective and review prisoner deaths as they come in to see if they were treated to the standards of the NHS and to offer recommendations for improvement. This year there has been a large increase in prisoner deaths or suicides so we will also look into the factors that may have led to this. However, I was cautioned that there is still a strong fraternal allegiance and protection among health care professionals left over from the days before the NHS, so to tread lightly as public and open blaming is strongly discouraged within medicine.

After returning from coffee Paul introduced me to the rest of the public health team. On the bottom floor are 4 or 5 women that handle the highly successful smoking cessation program. I promised to show them a hilarious poster featuring a superhero beating up a cigarette that I encountered on Barceona’s beaches. The next floor up hosts the STI crew who are hilarious and eager to share their dark humored sex jokes. They mistook the white geese on my tie as sperm and then insisted that I try on the “Chlamydia pants” or the Mr. Condom suit that they wear out for public events. I declined the pants primarily because I couldn't determine what plain looking pants had to do with Chlamydia. Up again, on Paul’s floor, are the county cooks, nutritional experts, Heather-the office manager of sorts, and a room of women dedicated to the various screenings that the island implements.

After lunch I had the awesome opportunity to sit in a meeting that took place in a pub (surprised?) between public health officials and the trust’s commissioners (essentially top name doctors who preside over different fields like surgery or accident and emergency, A&E). This meeting essentially fulfilled one of my key goals this summer which was to see how public health officials and physicians interact, argue, and form connections. There is some departmental loyalty but overall the groups seemed to mix well.

One limitation of government-run care was immediately evident as our 4 hour meeting concentrated on a great deal of overlapping evaluation systems the NHS requested from each Primary Care Trust. For example, there were 50 health outcomes (life expectancy, cancer survival rates, etc.) of which the island (and every other PCT) had to choose 8 and then pledge to improve them by 5% in 3 years. This of course could potentially allow the island to pick the easiest to improve and would not, at least in my inexperienced eyes, necessarily equate to better health. The public health officials wanted indicators like cervical cancer screening which has fallen lately while the physicians preferred lung cancer admissions rates which of course related to tangible issues at their hospital. The next evaluation system was a list of 192 data points the NHS requested each trust collect to evaluate its efficiency and ability to provide care. Finally, there was a third scheme that overlapped considerably with the other two but with different achievement targets and goals. And all of these schemes are dressed up with fancy public relations titles such as Joint Strategic Needs Assessment or World Class Commissioning. At the end of the very long meeting Dr. Bingham asked me in front of 25 top level officials for any suggestions and, after an uncomfortable delay, suggested that I go home and convince others not to let government take a hold of our health care.

My last lesson of the day concluded with an explanation as to why some doctors (like Dr . Bingham), who have an MD, are not referred to in person as doctors. Apparently anyone trained as a surgeon, or an OBGYN, after passing their review test are no longer referred to as Dr. so and so in conversation. Though in writing or on paper they are Dr.'s, in conversation a cardiothoracic surgeon would be offended if you preceded her name with that title. In addition, women are referred to as Ms. even if married and always by their maiden name. The reason lies with the origins of medicine in England with surgeons, university educated primary care doctors, and primary care doctors not trained at a university composing the three guilds. Due to competition and British eccentricism surgeons find Mr. a more prestigious qualification--though only in conversation of course.

No comments:

Post a Comment